Duende and the Machine

Editor’s Note: Hi All, I know it’s been a long time since the last post. My apologies. I have paused billing on subscriptions for the next six months. I will try to write more frequently during this time and then in six months I’ll decide whether to permanently end subscriptions and go to donations only or continue them. Cheers and thanks for reading.

Duende is a Spanish term that refers to a concept in art, particularly in flamenco music and dance, poetry, and other forms of artistic expression. It is a difficult concept to define precisely, as it encompasses a range of emotions and experiences.

Duende is often described as a profound, raw, and intense emotional state that can be evoked by a performer or experienced by an audience. It is a moment of deep connection and authenticity that transcends technical skill or virtuosity. When an artist possesses duende, their performance becomes charged with a powerful, visceral energy that captivates and moves the audience.

In flamenco, duende is associated with the expression of deep sorrow, pain, and passion. It is believed to be an elusive and mysterious force that emerges from the depths of one's soul and touches the hearts of others. It is considered the mark of a true artist, as it requires a deep understanding and connection to the art form, as well as a willingness to expose one's vulnerabilities.

Outside of flamenco, the concept of duende has also been explored in other artistic disciplines, such as literature and theater. It is often associated with a sense of authenticity, emotional truth, and the ability to evoke intense emotions in the audience.

Overall, duende represents the indescribable and enigmatic essence of art that goes beyond technique and skill, delving into the realm of passion, vulnerability, and profound human connection.

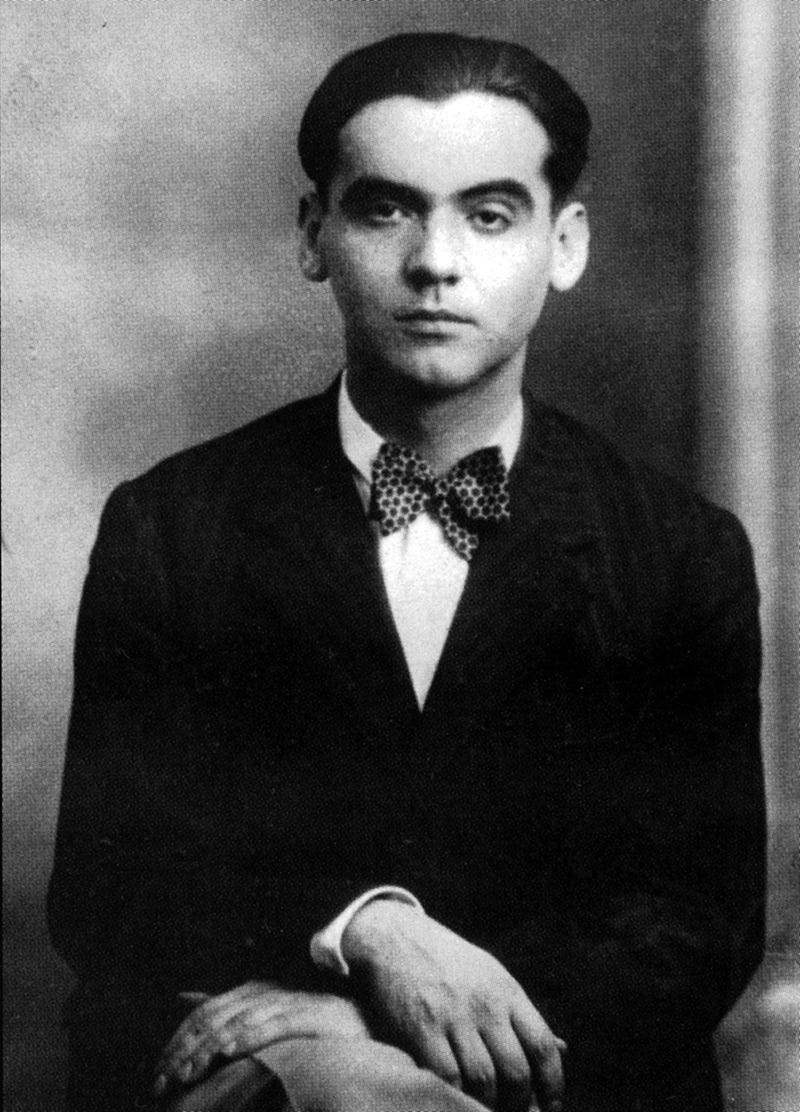

Could you tell the above passage was written by ChatGPT? I hope so. I hope my writing is not so stilted—an animatron wheezing to life in a regional novelty museum that unfathomably costs $40 to enter. The creator of the word, the great poet Federico García Lorca, had a much more lyrical definition in his brilliant speech "Theory and Play of the Duende":

"Those dark sounds are the mystery, the roots that cling to the mire that we all know, that we all ignore, but from which comes the very substance of art. ‘Dark sounds’ said the man of the Spanish people, agreeing with Goethe, who in speaking of Paganini hit on a definition of the duende: ‘A mysterious force that everyone feels and no philosopher has explained.’

So, then, the duende is a force not a labour, a struggle not a thought. I heard an old maestro of the guitar say: ‘The duende is not in the throat: the duende surges up, inside, from the soles of the feet.’ Meaning, it’s not a question of skill, but of a style that’s truly alive: meaning, it’s in the veins: meaning, it’s of the most ancient culture of immediate creation."

I encountered the concept of duende recently reading the program to a classical performance at the Walt Disney Center in Los Angeles earlier this year. I had flown out specifically for this concert—the legendary longtime conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Zubin Mehta, made a return to the podium at the age of 87 to guest conduct a few of his all-time favorite works as a farewell. Mehta is one of my favorite conductors, a kind of west coast doppelganger to Leonard Bernstein: handsome, passionate, brash, but truly gifted and rigorous. I own probably 20 of his recordings on cd and vinyl; his works represent the finest of American 20th century classical recordings, and true to his locale they are imbued with heat and brine. The first piece was George Crumb’s Ancient Voices of Children from 1972—a highly outré, avant work that incorporates Lorca’s poetry, sopranos, Tibetan gongs and bowls, Japanese rocks, and other unusual instruments accompanying a small orchestra section and piano. The piece is atonal at times, deeply melancholic and romantic at others (predicting some of Baldamienti’s work for David Lynch films), consummately haunting and electrically contradictory. It is one of the more alien pieces of music I’ve ever seen performed and still profoundly human—articulating the horrors of the Spanish Civil War as an eternal chorus of the innocent—a memento mori of all the cruel deaths of history, and the urgent quest of Lorca’s line in the piece: “El niño busca su voz”, “The child seeks his voice.”

The second piece was the early romantic classic Symphonie Fantastique by Hector Berlioz, which is a piece of program music—meaning it’s a symphony with a story--about an artist in unrequited love who purposefully overdoses on opium and begins a hallucinatory journey toward death. As Leonard Bernstein puts it: "Berlioz tells it like it is. You take a trip, you wind up screaming at your own funeral." It is also one of the platonic masterworks of 19th century European classical music—what you would play aliens to demonstrate romanticism. Mehta had the orchestra on a string, it was as if he had set up an incredible intricate musical Rube Goldberg machine, flicked the first domino, and reveled as it rippled and cascaded.

It is difficult to imagine any artificial intelligence or algorithm choosing these two pieces to pair together. If one did, I imagine it would solely be because of the record that Mehta was fond of both. It was his individual preference, his eccentricity, his duende in recognizing the duende of the two pieces 140 years apart—each seeking the spell of artistic echo and reflection to make meaning of the smoldering wreckage of life.

A few months later I returned to LA (just like Randy Newman sings “I love LA!”) for another spate of special cultural events. Up first was Ambient Church with Steve Roach. Roach of Temecula, California, is a pioneer of the ambient, new age movement of the early 80s in America. His albums have titles like Structures of Silence and Dreamtime Occurrence, they frequently employ digeridoos, rain sticks, and other instruments you would find at stores called Heaven on Earth (actual name of a new age catch all store in the town I grew up in). Until recently, Roach’s music was not particularly cool, but in the last decade of microdosing, palo-santo, sincere hipster belief in astrology, and the general existential dread percolating around us like rising cicadas, his serene, deeply cosmic music resonates and his recent series of “ambient churches” are well attended. I was supposed to go to one in Brooklyn in March of 2020, but it was obviously canceled due to Covid.

This one, in a hundred-year-old church in Koreatown, immediately set the mood, unfurling atmosphere like a Medieval tapestry. The swirling, psychedelic visuals were tailored for the space, often creating sophisticated optical illusions—the alter became a glowing abyss to eternity. Roach created all the music on synthesizers, sequencers, and other esoteric instruments. It’s true that one could imagine AI creating much of Roach’s music—especially the ambient synthesizer washes that have a massive, tidal quality—ebbing and receding in wine dark tones. But when Roach comes in on the didgeridoo or a wholly unrecognizable instrument that resembled a crossbow that shoots vibes, the music is unique, and the universe of new age platitudes takes form in sonic ritual. Roach made you believe. Can a machine ever do that unless it’s tricking you to think it’s human?

That idea was illustrated even more vividly the next day back at the LA Philharmonic in Frank Gehry’s whimsical concert hall which appears like a shimmering silver ocean fish by a cubist painter, a billionaire fairy-tale wish made material along the reflective anonymity of downtown LA. Despite its flashy exteriors, the hall is the best I’ve ever been to acoustically, designed by the legend Yasuhisa Toyota and carrying unamplified sound like a feather in a wind tunnel. I was there this time for an all-Mozart program: overture to The Magic Flute, Jupiter Symphony, and Piano Concerto #27, all late period works in the last year of his life, when he fell out of favor with the new emperor, a child died in infancy, and he was wracked by gambling debts and ill health. It was here I saw the greatest musician of my life—pianist Mitsuko Uchida. She played the notes in the concerto like a waterfall plays rivulets—perfection doesn’t do it justice, it was more whole than that, a kind of eternal naturalness. Piano is something which machine ability has long been able to technically match humans, you can buy a used Yamaha grand player piano that could play thousands of pieces technically perfectly for less than a shitty used car, but no one would pay several hundred dollars to see it “play” anything in a concert hall. The element of humanity is essential to our connection to art.

After the glorious Jupiter symphony in the second half, an elderly woman, clearly tremendously moved, said to me cheerfully: “I wish Mozart could see how we still love and revere his music.” Mozart was a preternatural genius, one of the clearest exceptions that proves the rule to the myth, whose name has become a noun unto itself for youthful, lightning strike talent (Mets pitcher Dwight Gooden was once described as baseball’s Mozart, UCLA math professor Terence Tao is nicknamed the Mozart of Mathematics). He was also a frivolous, undisciplined man—prone to drinking in excess, carousing, gambling, womanizing, and bawdy humor. The great film Amadeus isn’t particularly historically accurate (Salieri and Mozart were friends for example), but Tom Hulce’s brilliantly light and silly performance rings true. He apparently was like that—a daft fool who channeled heaven. The ineffable mystery of that contradiction is also essential to art and to existing as a human. As the great experimental filmmaker Ken Jacobs once said: “We’re so fucking smart and so fucking stupid.” Often at the same time. Upon the recent news that some AI program successfully passed the multiple-choice section of the bar exam for lawyers, I remarked to a lawyer friend that I would be much more interested if the AI had refused to take the exam for reasons unknown. Wake me when AI has a panic attack.

Next on my itinerary were a series of films at the American Cinemateque during the second year of their magnificent weeklong film series Bleak Week: Cinema of Despair, which delivers exactly what it promises—bleak, despairing, unsettling films that rarely get screened.

First was Lucrecia Martel’s La Cienaga, an incredibly assured debut about rich, drunken bourgeois ennui that eventually takes on a sulphuric, demonic tinge. Cienaga is Spanish for swamp and the film has a viscerally fetid and muddy quality, articulating the queasy foundations of western “civilization” through the simple physicality of a crumbling, decadent family drinking the heart out of the humid Argentina afternoons. If AI significantly improves, I could imagine feeding it La Cienaga, The Rules of the Game, They Shoot Horses Don’t They, and McCabe and Mrs. Miller and giving it a prompt like “wealthy dysfunctional family of ranking members of the British Raj spends a boozy weekend in a hillside estate in Assam on the eve of Indian Independence,” and it spitting out something serviceable. But wouldn’t there be something cynical and off-putting of an acerbic satire belched out by a computer? Doesn’t incisive art require the care of the creator to reflect on history, on society, on their own guilt and complicity, to cut to the quick and draw blood?

The second film of a Monday double header was a twisted white whale for me—the infamous 1986 Spanish film In a Glass Cage. I had heard of this film twenty years ago but was honestly too afraid to watch until a pristine 35mm print presented itself. To even type the plot feels scandalous: a Nazi pedophile who committed unspeakable crimes is hiding out in Spain and unsuccessfully tries to kill himself. Confined to an iron lung, he soon finds himself in the care of one of his former victims, eager to punish and also replicate his crimes. There are scenes in the film I still can’t quite believe they staged, it is breathtaking in the most heinous and evil way. Some might say this movie should be banned, that it is indefensible, and part of me agrees. But I can’t ignore its power, its shockingly refined Argento like craft (to make the nightmare all the more present, it was perhaps the cleanest repertory 35mm print I’ve ever seen), and its truly unblinking depiction of evil and depravity—positing a twin helix to trauma: that cruelty also passes down generation to generation epigenetically.

If an AI program generated In a Glass Cage, the program would almost certainly be shut down or altered. How could AI generated transgressive art be defensible? There would be no one to defend it. It would be like the twisted, perverse games the evil computer plays on the last humans in Harlan Ellison’s seminal short story about AI, I Have No Mouth and I must Scream. An omen to all this is the difficulty many AI engineers have in programming an AI chatbot that doesn’t almost immediately become a Nazi.

Finally the day I had been waiting for arrived, the main reason I had come out to LA for—to see Bela Tarr in person introducing the new 4k restoration of Werckmeister Harmonies and a film print of The Turin Horse. I have written about Bela in the past and my estimation of him has only grown. Currently, I am inclined to rank him equal with the greatest—Bergman and Tarkovsky. His vision—long takes, gallows humor, rain, mud, trudging through an existentially desolate landscape, a cosmic power to the bleakness of his tales underpinned by a refined sense of style that defines auteurism. No one does it like him. I even brought my Satantango blu-ray with a silver sharpie for him to sign. Before The Turin Horse I saw him outside, peacefully ripping a cig. Now was my chance! Just as I approached, Gus Van Sant appeared and chortled “Hey Bela….What have you been up to?” Bela exhaled a plume of smoke and sighed under the copper Santa Monica sunset: “Ehhh…Hollywood shiiiiit.” The “Hollywood Shit” he was referring to was probably just a dinner with enthusiastic American Cinemateque employees performing a film buff’s version of the Chris Farley show (“What was it like when you made your masterpiece Werckmeister Harmonies!?”) But I like to imagine Kevin Feige somehow roped him into a Marvel presentation ala the Tooth Fairy’s Slideshow in Manhunter (“This is our soulless antiseptic soundstage in Atlanta…do you see?”) as Bela squinted at the screen as if trying to read the model number on a vintage Boloflex camera. An American Cinemateque employee quickly ushered me away: “They’re old friends and they need to catch up.” I didn’t get another chance to ask him to sign it. It feels more poetically Tarr that the Satantango blu-ray cover shall remain black and my frivolous attempts at securing a memento were stymied by the universe.

Tarr’s style is so composed and stylized that on some level one could compare him to inimitable aestheticians such as David Lynch and Wes Anderson. With the advent of user AI, lots of dolts have started posting AI generated spoofs of directors with titles like “Game of Thrones if it were directed by Wes Anderson” followed by breathless comments “OMG perfect!!!” Some ghoulish Australian influencer on TikTok (I’m not going to bother to look her up) brayed: “And just in an instant anyone can do your genius, it’s almost saaaaad.” Of course, the spoofs are nothing remotely like an actual Wes Anderson film, they have some technical simulacra the same way a fridge magnet of Monet has with the actual waterlily panels at the Art Institute of Chicago. I have yet to see a single work of AI generated art that does not feel painfully derivative or else purposefully alien (the interesting yet hermetically sealed music of Holly Herndon that uses AI is an example). Wes Anderson is himself derivative, often quite intentionally, of Jacques Tati, Jacques Demy, and Karel Zeman, among many others, but he is a unique person, with a unique taste, his pastiche is his own personalized calibration.

I believe we have been living in a sort of soft opening of AI for several years at least with music and film/television. The proliferation of guided automation of many technical aspects that used to require much more painstaking direction and effort (Lighting shows/movies via CGI in post, quantizing and autotuning music etc.); the mining of tired existing properties, remakes, and gimmicks; and the adoption of a kind of cultural sabermetrics—Netflix often employs this, running shows through algorithm of metrics that then dictates what sort of shows they should make with what kind of plots etc—have created cultural products not dissimilar from the lab tested monstrosities of fast food—designed to give us what we want—sugar, salt, and fat. It doesn’t matter if it leaves no impression other than dulling our senses—it’s addictive, it’s easy, you can binge it.

If there’s a silver lining to all this, it does seem that people are more appreciative and receptive to human works. The two smash hits of the summer—Barbie and Oppenheimer would not have succeeded without the people behind them. If Barbie had been made in the Marvel style—journeyman director, produced to be maximally frictionless—it would have come and gone as another cynical, misguided, barrel scraping gambit and industry observers would suspect that it was all actually a money-laundering ruse. Instead, it is a global cultural phenomenal, one that will earn the Warner Brothers billions of dollars. And this is all because Greta Gerwig collaborated with talented, professional, creative people who built real sets and sewed real costumes. She took inspiration from MGM musicals, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, All That Jazz, disco music, and The Truman Show, and she wrote a meta, funny, and surprisingly moving script with her partner—the prickly, urbane filmmaker Noah Baumbach. In other words—she had a take, a vision.

My final cultural adventure of the summer took me to Manhattan en route to a friend’s wedding in Vermont. I made my first pilgrimage to the legendary West Village Jazz Club, The Village Vanguard. The Vanguard, which opened in the 1930s, has hosted thousands of legendary performances, hundreds of which have been preserved by recording (Albert Ayler and John Coltrane in the 1960s are two of many, many highlights). It is undoubtedly home to some of the greatest music that’s ever been played, up there with Carnegie Hall and Royal Albert Hall. Little has changed over the years—it’s remained endearingly rustic and unfussy. A basement club with a capacity of 130, a simple bar and table service, and a solid sound system. And yet what is conjured in that humble place represents the pinnacle of improvisational human creativity.

I went with a couple friends to see Bill Frissell’s quartet. Frissell at 70 has achieved an esteemed place in American music, able to play it all, Beatles covers, film scores, free Jazz, nonesuch folk with his inimitable delicacy and grace. His quartet played a bruised and haunted Appalachian Jazz blues, lilting between canonical folk tones and wandering improvisations, finding the charged space in the labyrinth of memory and letting it thrum back like a string through the maze. I was riveted, the entire crowd was riveted, dead silent, reverential, this was a living, deeply American folk-art ritual—as refined and elegant as it was defiant to any possibility of replication, automation, or imitation. It was only here, in this hallowed space, in this moment, and never again.

The piquancy of this frequency by its very nature resists our AI overlords that seem to demand t they get to dream while we do the boring, soul-deadening rote work we always imagined machines would eventually take over leaving us to dream. But no, we have to make money by working, even if that means artificially suppressing technologies that offer automation (like self-driving long-haul trucks, or field harvest) because that is the intrinsic logic of capital, which is the dominant religion of the world. And so, the things that don’t make money: like art, music, writing etc., can be more easily automated. It’s a strange and horrible emerging dystopia that even our most fried sci-fi visionaries like Philip K. Dick and Aldous Huxley didn’t imagine.

In the artist and writer Victor Burgin’s illuminating reflection on Benjamin’s Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, he writes:

Around 300 BCE, the Chinese philosopher Zhuangzi imagined a confrontation between a disciple of Confucius and a Daoist gardener. Having watched the gardener laboring with a rudimentary and inefficient means of watering his plants, the Confucian informs him that a machine exists that can water a hundred fields in a day with much less effort. The gardener replies that whoever uses such a machine will have a mind like a machine, and that whoever views the with such a mind will lose oneness with the world.

On some elemental level, I believe this, and I suspect we all do. But we mostly are powerless to this siren song. I have no doubt that AI will be used more and more by artists, that I myself will use it more and more, and that just as my sense of direction has eroded to where I find myself checking my phone’s GPS for places I know by heart, other faculties will erode into a model train circuitry—turn them on and it goes in a circle. But I will try to remember and engage with duende, it is the closest thing I have to a religion, but I don’t need faith because miracles are all around me all the time. In the last few months alone: seeing Persona and Werckmeister Harmonies in a particularly potent double header, a piano concert of Rachmaninoff’s works for his 150th birthday including romantic songs adapted from Pushkin and Tolstoy poems, and a global jazz concert under a bridge on the San Antonio river. Even in the relative “hinterlands” duende is all around. This is what I shall remain invested in regardless of future technological marvels that march and tilt at us from the light blasted horizon. Because this is what makes me feel alive; and even if human consciousness eventually extinguishes, works of duende will be the doo-wop radiating off the dash radio as we round dead man’s curve.

Frank Zappa once remarked that there was nothing quite like the sensation of hitting a doo-wop harmony right, locking it in, making it vibrate like the music of the spheres. With a single keystroke you can create any perfect harmony and soon, through deep-fakes and AI, you’ll be able to have any famous musician sing any song for you—Freddie Mercury can croon “Moon River” to sooth you when polar bears go extinct. Plato’s Allegory of the Cave has come true yet again, and soon we will find ourselves dwelling in endless labyrinthine caves, watching an endless dance of digital death thinking this is real. Enjoy the sunlight and its burn and its glare while you still can.

Playlist: Wes Montgomery

I’ve recently been obsessed with the impossibly elegant jazz guitarist Wes Montgomery whose life and music are lapidary examples of duende. Born in Indianapolis, living an extremely hardscrabble, working-class life, Montgomery was self-taught and developed his unusual style of strumming the guitar with his thumb to keep quiet when he practiced late into the night after his factory job. That he made such beautiful, rarefied music that transfixed audiences around the world is a miracle of creativity. Here’s a brief mix of some of my favorite of his songs. Youtube/Spotify

Movie: Straight Time

Rewatched this with some buddies recently and it endures as a stone cold bleak 70s classic featuring Dustin Hoffman at his most high T and feral. Hoffman plays ex-con Max Dembo who is relentless ground down by his sadistic PO (M. Emmet Walsh) before finally snapping and going back to the old me. A stacked cast (Harry Dean Stanton, Kathy Bates, Theresa Russell, Gary Busey), beautiful cinematography and a groovy David Shire score make this a perfect, thrilling slice of California hangover ennui. (Amazon)

Book: Heat 2

I finally read Michael Mann’s and Meg Gardiner’s novel sequel to the 1995 crime classic film Heat and was stunned by how much it exceeded my expectations. Just like the film, the book is steeped in a cokey, Zen stoicism—the characters are always “locked in”, “scanning the room”, “riding their pulse” etc. The bad guy is basically an exact copy of the serial killer neo-nazi Waingro from the first film, but why mess with a winning formula? I really hope he gets to make a movie of this with Austin Butler as Chris Shehirlis, Adam Driver as a young Neal McCauley, and Jeremy Allen White as Vincent Hanna. (Amazon)

Parlor Game: The Toy Adaptation Game

After Barbie, there will be an absolute tsunami of toy movie adaptations and many will try to have some high concept like Barbie. The result will be perhaps the most pretentious pitches in the history of studio filmmaking. For this game you pick a recognizable toy, then pick an art movement, then pick a genre/subgenre, then pick two films/filmmakers, novelists etc. For example: “We’re making Hot Wheels, it’s going to a kind of fauvist road movie, like Robbe-Grillet meets Two Lane Blacktop; or, “the My Buddy movie is a go, it’s going to a surreal fable, think Being There meets the Tin Drum.

Yes! Welcome back. Gaaaaaaaaah this is good. You gnaw at some of the shit that keeps me up at night about the future for my 7 y.o. … How will her gen deal with the raw horrors of life when they can’t even fathom being bored in the dentist’s office for 10 minutes without a digital pacifier.

Wake me when AI has a panic attack LOL thank you for that.

PLEASE keep writing!